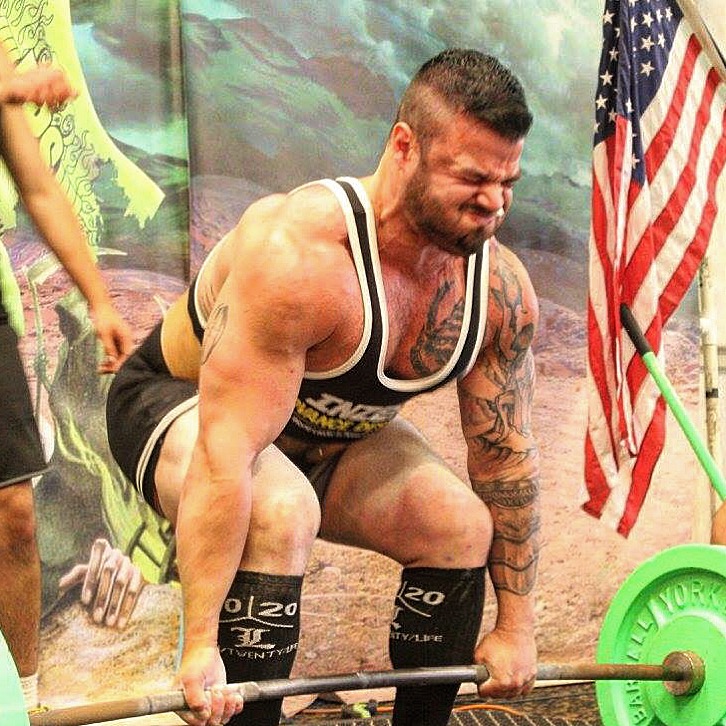

20 Jul Progress is a Process

By Paul Oneid

Something that rarely gets discussed is the process by which we progress movements during training. We know that from a meet preparation standpoint, training should be more specific to the competition movements and during the off-season, the movements should be more general. Now, if you subscribe to the notion that your training should be as specific as possible all the time, then so be it, but I wish you good luck. Training variety lends itself to building a well-rounded physique, base level of conditioning and it prevents training from getting stale over time, among other more nuanced benefits. The process by which you progress, regress and swap movements in and out will be dependent on your goals and the timeline, but some general guidelines should apply.

The further away from the meet, the more general training should be. This holds true for movement selection, energy systems and absolute intensity alike. You should be aiming to perform more volume with lighter weights on movements that resemble the competition movement. Relative intensity should be high, but absolute intensity should be low. How does one accomplish this? You choose movements that challenge your weaknesses. As you train in this manner, your proficiency in the movements improves, your work capacity improves and your weaknesses become less weak. If you follow the site, you know this isn’t new information. But, how do you get from the general to the specific in an intelligent manner? You do so by systematically bridging the gaps.

First, you must progress the loading parameters. This is accomplished through increases in volume first, followed by intensity. Increase the amount of work you do, then increase how heavy that work is. As the absolute load increases, you’ll be able to match up the relative intensity and absolute intensity of a different movement. We know that intensity and volume should undulate, so this method works perfectly. Performing ten working reps at RPE 9 of a challenging variation should match up to the relative intensity of 20 reps of a less challenging movement. From there, you can increase the volume and intensity in the same manner before you swap the movement again.

Next, we need to look at the movement itself. What makes one movement more difficult than the next? Typically, it is either altering the length of the ROM (buffalo bar vs. board pressing) or altering the center of mass (Cambered bar vs. high bar). The longer the ROM and the further away the bar from the center of mass, the less weight you’ll be able to handle. There are plenty of examples, and the choice of movement would be based on the needs and weak areas of the specific lifter. As you progress the volume and loading parameters, shorten the ROM, or bring the center of mass closure to the body.

Other considerations would be altering the time domain, or time under tension of the movement, such as introducing a tempo or pause work. You can alter the velocity curve of the movement through accommodating resistance. You can also alter the density of the training by manipulating rest periods. Whatever you choose, be wary because the more manipulations you make to the training, the more methodical you must be in progressing back to the competition variant.

Accessory work should follow an inverse pattern regarding both absolute and relative intensity. As the main movement of the day gets heavier and more intensive, the accessory work should become less intensive. The volume of accessory work should also decrease as more energy and recovery reserves should be devoted to the main work. Varying the loading mechanism, time domain and ROM are an integral part of planning accessory work. They should address structural balance, weak points and aim to preserve movement qualities that may be lost as training specificity increases.

While this may seem overly complicated, it does not have to be – you have to PLAN! Once you know how much time you have before the meet, you’ll know how long you have to progress variations before meet prep. If you follow the principles espoused in 10/20/Life, a 10-week meet prep is sufficient. During meet prep, specificity is king, and the main movement is the priority. The first assistance movement should be a close variant chosen to address weak points. This movement can change over time, and as the meet approaches and absolute intensity of the competition movement rises, it will be eliminated to facilitate recovery. This means that at ten weeks out, training variety should be next to non-existent. Using the example of a 10-week prep, you could likely progress two movements, but the longer the off-season, the more variations you could use.

Here is an example of a 10-week Off-Season progressing two squat movements:

Week 1 – SSB 5×5 RPE 7; Front Paused 4×5 RPE 7

Week 2 – SSB 5×5 RPE 7; Front Paused 4×5 RPE 7

Week 3 – Comp Squat – Deload

Week 4 – SSB 5×5 RPE 8; Front Paused 4×5 RPE 8

Week 5 – SSB 5×5 RPE 8; Front Paused 4×5 RPE 8

Week 6 – Comp Squat – Deload

Week 7 – High Bar 5×5 RPE 7; Front Squat 4×5 RPE 7

Week 8 – High Bar 5×5 RPE 7; Front Squat 4×5 RPE 7

Week 9 – Comp Squat – Deload

Week 10 –High Bar 5×5 RPE 8; Front Squat 4×5 RPE 8

Begin Meet prep

Week 1 – Comp Squat 5×5 RPE 7; High Bar Paused Squat 4×5 RPE 7

Week 2 – Comp Squat 5×5 RPE 7; High Bar Paused Squat 4×5 RPE 7

Week 3 – Unequipped Comp Squat – Deload

Week 4 – Comp Squat 5×3 RPE 8; High Bar 4×3 RPE 7

Week 5 – Comp Squat 5×3 RPE 8; High Bar 4×3 RPE 7

Week 6 – Unequipped Comp Squat – Deload

Week 7 – Comp Squat Singles RPE 8

Week 8 – Comp Squat Singles RPE 9

Week 9 – Taper

Week 10 – Meet week deload

Progression should not be done on a whim. Planning your progressions will ensure a seamless transition from general to specific, allow you to accumulate the appropriate amount of volume required to improve your weak points and allow you to peak your strength when it matters – on the platform. Be methodical in your implementation. Progress is a process.

Learn how to TRAIN YOURSELF LIKE A PROFESSIONAL COACH – for the rest of your life!

20 YEARS OF RESEARCH AND TRIALS distilled into a philosophy you can actually use!

Get INSIGHT INTO THE MENTAL GAME of training and nutrition from the guy who’s been there and done it.

Paul Oneid

Latest posts by Paul Oneid (see all)

- A Proposition for a Paradigm of Planning Your Personal Periodization - March 4, 2019

- Paul Oneid –> Off-Season | Feet Up Bench PR and Some Squats - March 1, 2019

- Paul Oneid –> Off-Season | A bit of everything - February 21, 2019

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.