15 May Engineering A Better Total

By: Dan Dalenberg

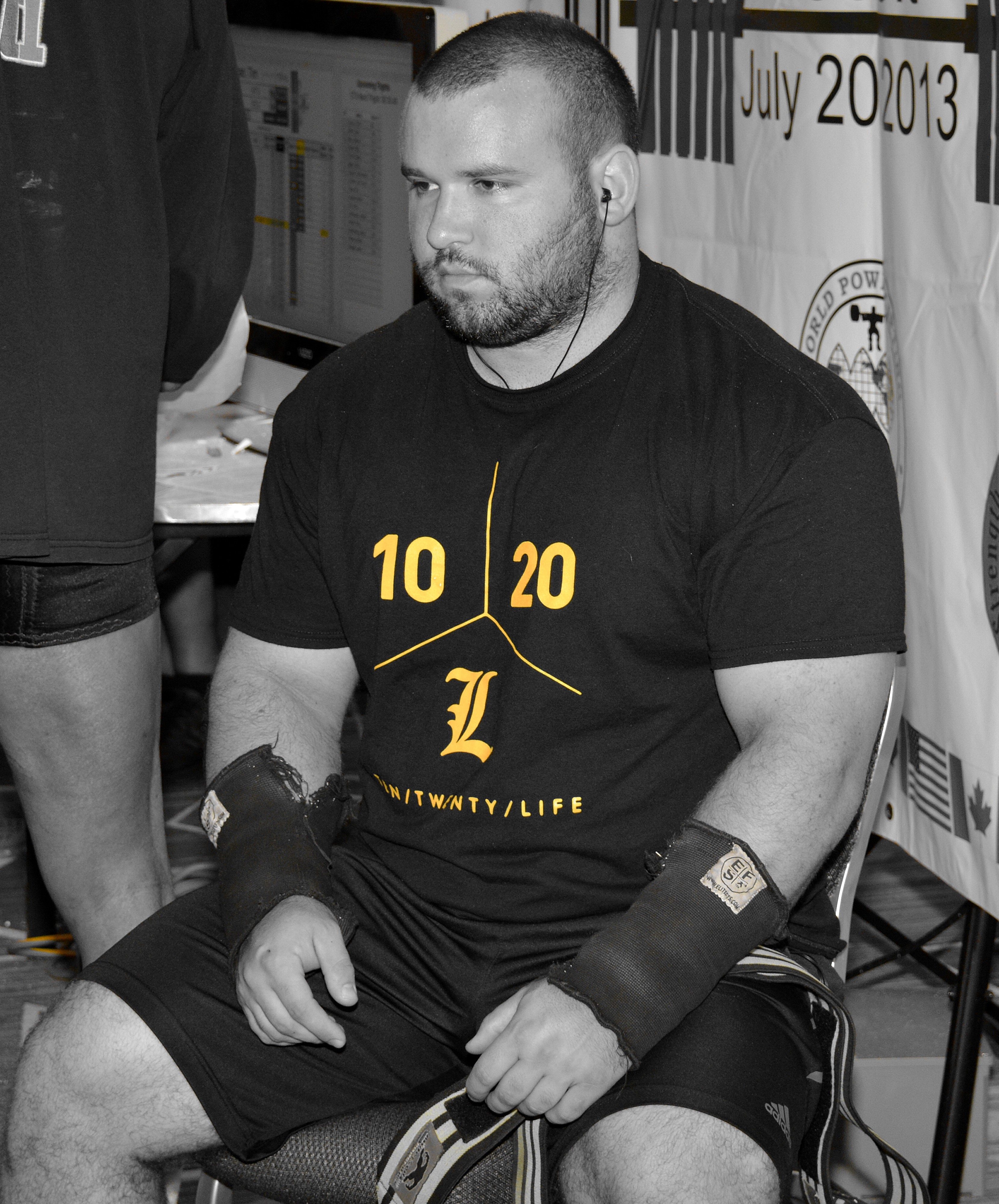

I’m a nerd. I went to a small, private nerdy college with a bunch of other people that Scott and Brian probably bullied all through grade school and studied nerd stuff. My degree is in mechanical engineering and I work as an Advanced Quality Engineer for a medical device company, Stryker Instruments. AQEs do a lot of different things for our organization but really the job boils down to 2 main categories:

Risk Management– Determining how product can fail and how those failures effect the end user or patient and ensuring the benefits outweigh the risks

Design Validation– Making sure that we designed products that actually meet the user’s needs

I’m fairly good at my job, this is what I live and breathe from 8-5, 5 days a week. Sounds really boring I’m sure. One would think that my engineering career is entirely separate from powerlifting, but that simply isn’t true. Applying these same concepts and thinking about training, coaching and competing in the same way that I think about medical devices has made me a better lifter.

Risk Management

This needs to be broken down into two topics, risk management for both competition day and for training.

Training Risk

If you are a serious lifter and don’t believe that there is risk in training I’d really like to hear from you and discuss that. Lifting at a high level will always present risks and many would argue it’s not a question of if you get injured, but rather when.

As a result, we must minimize risk in training; the benefit of what you are doing must be weighed against the risk. I apply this concept to both the movement that I choose as well as how intense my sessions will be.

Movement Selection

Consider the benefit of a movement compared to its risk. If you are a baseball player, a pitcher, would you want to be doing a ton of heavy flat bench pressing? Maybe not, the risk of over stressing your shoulders probably outweighs the benefit. If you are a powerlifter, should you be doing a ton of Olympic lifts? I’m going to answer that with a “No” I just don’t think the benefit is worth the risk of injury or overtraining since those movements don’t typically directly benefit powerlifters.

Intensity

This is simple. Where are you at in your training? If you are 19 weeks out is there really a point in subjecting yourself to a bunch of grindy, slow max effort lifts? I would argue no, that you would be better off not risking injury and working off of the RPE scale to allow your body to be fresh and ready to go when it really matters- towards the end of a training cycle.

Competition Risk

At the end of the meet, the only number that actually matters is the total. No one will care if you squatted 850 but then bombed on the bench, you lost. You scored 0, your squat didn’t count and the guy that totaled 2200 beat you by 2200. So minimize risk to your total and always have that end number in mind.

When selecting attempts I believe that it is always important to have an idea of where you want to finish and have a plan B to get there. Attempts must be set up smart to allow for a plan B and at times may feel a little conservative. For example, at RUM8 all I wanted to do was PR my total, I wanted to go over 2000 again. I knew to do that I would need an 800 squat. Going into my third attempt I felt like 825 or so would go, but I knew I needed 800 and felt very confident that 804 would move well. It did.

I know some would think I am a pussy, why didn’t I go 821? Well if I went 821 and missed, I would be stuck with a 760 squat and be missing 61 pounds off my total and 2000+ is probably out of reach. However, if I go 804 and smoke it, 821 would’ve gone, but I’m only missing 17 pounds off my total. 2000+ is absolutely in reach. Point is- don’t shoot for the moon just to take a big attempt. Pick that third attempt based on what you want to total at the end of the day.

Training Validation

This is a much shorter but even more important area. Design validation is making sure the product is designed to meet the user’s needs. Training validation is ensuring that the lifter is designing a training cycle that actually meets their needs and will build up their weaknesses.

We love training gadgets. Many of us love a little torture too. So often I hear people say “I want to do that- it looks hard!” This is common too- “that new bar or implement that Rogue makes is really cool, we should buy one.”

Those things might in fact be very useful if you actually need them. You could write a super challenging training cycle with lots of crazy movements but it won’t be anywhere close to as effective as one written with your weaknesses in mind. Validate your training cycle by really thinking about your weaknesses and missing points before writing it. Choose exercises based on the results of that analysis. The resulting training might not be cool but will almost surely be more effective. Gym hero or a bigger total, what’s your pick?

In Summary

Powerlifting doesn’t have to be just a bunch of meatheads slanging weights around. Nor should it be made over complicated. Find a happy medium applying the concepts discussed above, throw in some common sense and I believe you will be setup for longer, more successful lifting career.

GET THE 10/20/LIFE EBOOK HERE!

Daniel Dalenberg

Latest posts by Daniel Dalenberg (see all)

- A Binge for the Record Books - August 20, 2018

- Training on the Go - July 6, 2018

- Dan Dalenberg | Deload and 5k week! - June 18, 2018

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.