- Pain-free does not equal healed—recovery requires patience and gradual rebuilding.

Repeating pain triggers too soon is like “picking a scab” and delays healing. - The spine is a “black box,” so progress must be tracked through milestones, not guesses.

- True recovery demands discipline, trust, and respect for biological timelines.

The Misconception of “Pain-Free”

One of the hardest lessons for people dealing with back injuries is understanding that pain-free doesn’t mean healed. In my own journey, I learned this the hard way. After being out of pain for months, I assumed I was in the clear and pushed too fast. The reality is that the absence of pain doesn’t mean your tissues have fully recovered or adapted to handle the demands of heavy training, work, or even daily life.

Too often, I see lifters, soldiers, and weekend warriors get pain-free and rush back into their old habits. Within months, they end up right back where they started—or worse. Healing requires time, patience, and a progressive rebuilding of capacity. For me, it took 18 months before I was ready to handle the brutal forces of squatting, benching, and deadlifting at the highest level again.

Spine Hygiene and “Picking the Scab”

Dr. Lysander Jim echoed this exact struggle in our conversation. He described it as “picking the scab.” Just because pain has wound down, people feel tempted to test their trigger movements—to see if the pain is really gone. But like reopening a wound before it scars over, this delays healing and sometimes causes even greater setbacks.

Dr. Jim writes about this in his own work on spine hygiene, emphasizing the importance of avoiding pain triggers even when you feel better. He warns that mistaking a pain-free back for a fully healed one is one of the most common barriers to recovery.

The Black Box of Healing

One of the challenges with back injuries is that you can’t see the healing process. Unlike a surgical incision where you can visually track scarring, the spine is hidden—a “black box,” as Dr. Jim puts it. Patients rely on feedback from their own symptoms and the interpretation of their clinician or coach.

The problem is that our culture celebrates pushing through, grinding harder, and refusing to back off. High-achieving individuals—athletes, professionals, soldiers—often excel because of this mindset. But biological systems don’t follow the same rules as business growth or technology. You can’t force a faster recovery. You can double your revenue in a year, but you can’t double your healing speed.

The Role of Credibility and Trust

Something Dr. Jim pointed out that resonated with me is the power of credibility. When patients hear the “slow down” message from someone who has been under the heaviest weights in the world, it carries weight. As he said, he can explain the same principle, but some people listen more closely when they hear it from me—a powerlifter who’s lived it.

Still, even with the best coaching, some people resist. Some come in skeptical, never fully trusting the process. Others want a crystal-ball prediction: How long until I’m healed? When can I get back to normal? The truth is messy. Some recover quickly, others need surgery, and many fall somewhere in between. Honest coaching means balancing realism with hope.

Progress Measured by Milestones

The most practical takeaway is to stop looking for an exact finish line and instead focus on milestones. Can you get through your daily activities without pain? Can you perform spine-sparing movements consistently? Each checkpoint builds confidence and capacity. That’s how recovery is earned—not by skipping steps, but by stacking small wins over time.

Final Thoughts

Both Dr. Jim and I see the same struggle: people confuse pain relief with true healing. It’s human nature to want quick answers and faster timelines, but the spine doesn’t work that way. The process requires discipline, trust, and patience. Whether you’re a competitive lifter, a soldier, or a weekend athlete, the principle remains the same—respect the biology, avoid your triggers, and earn your progress step by step.

Article Rundown

- Pain-free does not mean healed.

- Build pain-free capacity before chasing performance.

- Layer resilience with gradual, progressive exposures.

- Keep early principles intact while rebuilding toward goals.

The Phases of a Proper Rebuild: Respecting the Process

When it comes to rebuilding from a back injury, there are no shortcuts, magic tricks, or quick fixes. I’ve lived it myself after splitting my sacrum (as outlined in Gift of Injury), and I’ve walked hundreds of people through the process of reclaiming their lives and athletic performance. While I draw heavily on Dr. Stuart McGill’s methods, I fuse them with my own experience in strength training, coaching, and rehabilitation.

One thing I need to make clear up front: I don’t speak for Dr. McGill—or anyone else but myself. What I share is what I’ve lived and what I’ve used successfully with others. And the first truth we have to confront is this:

Pain-free does not mean healed.

I see it every week. Someone feels better after a week or two, then goes straight back to squatting 225, playing 18 holes of golf, or grinding through hours of pickleball—only to crash harder than before. This “flare up, crash, repeat” cycle happens because people don’t understand the phases of rebuilding. So let’s break it down.

Phase One: Remove the Cause and Build Pain-Free Capacity

The first step is desensitization. Before you think about lifting heavy, you need to understand and eliminate the very movements, postures, or loads that cause your pain. This is where the McGill assessment is invaluable: we identify your pain triggers and then remove them.

From there, we start building pain-free capacity. That means retraining movement patterns, using proper posture, and programming exercises that don’t provoke your injury. Precise walking mechanics, tuned—not braced—core stiffness, and staples like the Big Three (with appropriate variations) all play a role.

The hard part is learning not to “pick the scab.” If you keep poking at pain triggers, you’ll never wind down the sensitivity. Many people struggle with this because they equate “no pain today” with “I’m cured.” But the spine is not a pec or a quad—it involves discs, nerve roots, ligaments, and joints that need far longer to remodel and adapt. Muscle might recover in a day; bone takes five. Discs and supporting tissues often require months.

So if you’re pain-free for 10 days and then max out your squat, don’t be surprised when the pain comes roaring back. You skipped the work of actually earning capacity.

Phase Two: Build Resilience and Redirect Toward Goals

Once pain-free capacity is established, the next stage is resilience building. This is where we progressively expand what you can do while keeping symptoms at bay. The mistake many lifters and athletes make is skipping this stage because they “feel good.”

Think of it like golf: you don’t go from two weeks of pain to immediately playing 18 holes. Instead, you chip a few balls, add more exposures slowly, and build up to full play. The same goes for lifting—you don’t deadlift max weights just because you had a couple of good days.

Resilience training depends on your goals. For some, it’s returning to the platform. For others, it’s picking up their kids without pain or getting back to a recreational sport. Phase two might involve dumbbells, kettlebells, sled drags, or carries. The tools change, but the principle stays the same: layer in progressive exposures that bridge the gap between pain-free living and performance.

Phase Three: Rebuild Toward Specific Performance Goals

The final stage is where the real payoff comes. Phase three is about keeping the integrity of phases one and two while beginning to rebuild toward your specific goals.

This means that you don’t abandon pain-free patterns or resilience work—you carry them with you. But now you carefully layer in the demands of your sport or activity. For a lifter, that may mean gradually adding back squatting and pulling patterns. For a golfer, it could mean progressively restoring full rotational capacity. For someone who simply wants to live without pain, it may be as simple as returning to full days of work, travel, or childcare without setbacks.

Here, the art is in balancing progression with protection. The foundation remains the same—remove triggers, stay pain-free, expand resilience—but the application becomes goal-driven and personal. Done right, phase three allows you to return not just to normal life, but to the things you love most, at the highest level you can sustain.

Why Respecting the Phases Matters

The spine doesn’t play by your rules. Biology is binary—it adapts on its own timeline, not yours. If you skip steps, you’ll pay for it. That’s why I caution anyone who’s told, “You’ll be back under the bar in two weeks.” Be skeptical. That’s not how spinal adaptation works.

The people who come to see me in Jacksonville aren’t the ones who just got hurt yesterday. They’re the ones who’ve lived in pain for 10, 20, even 40 years, trying every shortcut before finally realizing they need to respect the process.

When I work with someone in person, I spend two full days assessing, winding down their pain, and workshopping the right exercises. They leave with a plan, video coaching, and clear progressions—not just a cookie-cutter rehab sheet. That’s the level of detail it takes to truly guide someone from pain to performance.

The Bottom Line

If you want to break the cycle of flare-ups and setbacks, you must respect the phases:

- Phase One: Desensitize, remove the cause, and build pain-free capacity.

- Phase Two: Expand resilience and begin layering progressive exposures.

- Phase Three: Maintain the first two phases while rebuilding toward your specific goals.

Skip steps, and you’ll keep repeating the same mistakes until your back gives out for good. Respect the process, and you can return not only to lifting and sport but to a stronger, more resilient version of yourself.

Lessons I Shared with MOPs & MOEs

When you’ve been around strength sports long enough, you start to realize that pain and setbacks are part of the process. For me, that reality hit hard in 2009. I was already a decorated lifter with world records under my belt, but one misstep—literally hurdling a barricade while preparing for a police academy scholarship—changed my life. I came down wrong, hurt my back, and entered into a battle that would define the next stage of my career.

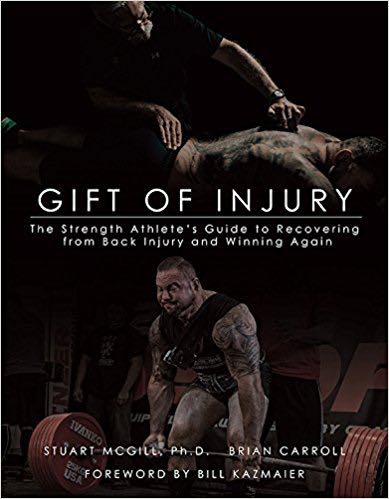

On the recent MOPs & MOEs podcast, I had the chance to share that story, talk about what I learned, and dig into the lessons from my book Gift of Injury, which I co-wrote with Dr. Stuart McGill. What started as my personal rehab journey turned into a mission to help others avoid the same mistakes I made.

From Records to Rock Bottom

By 2009, I had established myself among the best in the sport. I had totaled 2730 at 275 and 2651 at 242, lifted more than ten times my body weight across three weight classes, squatted over 1000 pounds more than 60 times, and became the first man to squat 1300 pounds. My all-time world record squat of 1030 at 220 cemented my place in powerlifting history.

But none of those numbers could protect me from the consequences of poor movement patterns, stress concentrations, and pushing through pain. When my back gave out, I went from chasing records to barely being able to train. Like many athletes, I thought I could grit my way through it. That mindset nearly cost me not just my lifting career, but my quality of life.

Finding the Right Guide

In 2013, I reached out to Dr. Stuart McGill. That decision changed everything. Instead of surgery or quick fixes, Stu gave me a framework: assess the injury honestly, rebuild from the ground up, and create a plan that not only restored my back but made me more resilient than ever.

The process was humbling. I had to learn how to move differently, manage stress, and rebuild strength in a way that respected the injury. But the payoff was massive. Not only did I come back to the platform—I hit my historic 1306-pound squat after my back injury and rehab with Dr. McGill.

That’s the real message of Gift of Injury: setbacks don’t have to be the end. They can be the beginning of something even greater if you’re willing to put in the work.

A Healthy Debate on MRI and Back Pain

One of the interesting moments on the MOPs & MOEs podcast was a discussion I had with John, their in-house rehab expert, about MRIs. At first, it seemed like a debate about whether MRIs are useful in diagnosing back pain. The truth is, it was more of a miscommunication.

MRIs can show structural changes, but they don’t always tell the full story of someone’s pain. A scar on a scan might be old and healed, yet a surgeon could still chase it with the knife—missing the real issue. That’s why assessment, movement patterns, and a full understanding of the individual matter so much more than just relying on images.

It was a productive conversation, and I look forward to revisiting it with John in a future episode. These discussions are what move the needle forward in strength and rehab: lifters, coaches, and clinicians sharing ideas and challenging assumptions.

Where I Am Today

These days, my focus is broader than just numbers on the bar. Through my coaching and consulting business, Power Rack Strength, I work with lifters, athletes, and rehab professionals to apply the lessons I learned the hard way. I still love chasing strength, but my mission now is helping others train smart, stay healthy, and avoid the pitfalls that nearly ended my career.

Gift of Injury continues to resonate with athletes and clinicians because it’s not just about my story—it’s about a roadmap for anyone struggling with back pain and wondering if they’ll ever lift again. The answer is yes, if you’re willing to commit to the process.

Final Thoughts

I’m grateful to the MOPs & MOEs team for the chance to share my journey. Pain doesn’t discriminate—it doesn’t care if you’re the strongest person in the world or a weekend warrior. What matters is how you respond.

If my story can help even one athlete avoid the mistakes I made, then the injury that once felt like my biggest setback becomes part of my biggest contribution.

Check out the full episode of the MOPs & MOEs podcast [HERE] for the complete conversation.

Article Rundown

- Dr. Lysander Jim connects spine health with chronic inflammation and hidden illnesses like Lyme disease.

- Unexplained back pain can sometimes signal underlying immune or inflammatory issues.

- Chronic pain doesn’t just hurt the body — it can actually change brain structure and function.

- Collaboration between biomechanical coaching and medical insight leads to a more complete recovery.

Two Worlds Colliding

One of the things I love about the “Gift of Injury” project and the work we do through PowerRackStrength is bringing together experts from different fields who care about the same mission: helping people get out of pain and back to performing at their best. That’s exactly why I sat down with Dr. Lysander Jim, a physician based in Beverly Hills who has spent the last several years working with patients dealing with spine pathology, chronic inflammation, and what many people would call “mystery illnesses.”

Dr. Jim explained that while a significant portion of his practice is devoted to spinal curves and related issues, most of his patients come to him with environmentally related illnesses — especially mold exposure — or symptoms that other doctors haven’t been able to explain. “It kind of fluctuates,” he told me. “But I’ve gained a bit of a reputation for figuring out these unexplained symptoms and conditions.”

When Pain Doesn’t Add Up

As a lifter and coach, I know the usual timelines of recovery from injuries like disc bulges. Often, after six to eight months, the body adapts and symptoms should calm down. But as Dr. Jim pointed out, sometimes things don’t line up.

“We’ll have a client where the imaging shows a disc bulge that should be winding down, or maybe a little bit of facet irritation,” he said. “But they’re still having pain that’s out of proportion to what we’d expect.”

That’s when Dr. Jim started noticing a pattern: some of these patients weren’t just dealing with a spine injury — they were also dealing with systemic inflammation from underlying conditions like Lyme disease.

Lyme Disease, Inflammation, and Recovery

Lyme disease, as Dr. Jim explained, is most commonly transmitted through tick bites. The tricky part? The ticks that carry it are often so small that people don’t even realize they’ve been bitten. He added that there are also theories about in-utero and even sexual transmission, though tick exposure is still the most recognized cause.

What makes Lyme so problematic is how it interacts with the body. “These bacteria literally eat their way into tissues,” Dr. Jim said. “That’s why so many patients complain of knee pain. On top of that, it triggers a massive inflammatory response. So any injury you already have — like a disc issue — is going to hurt worse, heal slower, or maybe not heal at all.”

He shared a case where a patient with a disc bulge should have been recovering, but every small misstep sent pain shooting from the spine all the way up to the head. “That kind of symptom doesn’t fit the usual mechanical pattern. That’s when you start to suspect something deeper — a chronic infection or an immune system issue.”

Once those patients were tested, Lyme disease was confirmed. From there, Dr. Jim referred them to Lyme-literate physicians who could address the root cause. Only after that underlying inflammation was managed did the biomechanical interventions — things like spine hygiene, proper movement, and targeted coaching — start to really take hold.

Chronic Inflammation: The Silent Roadblock

One of the most powerful takeaways from our conversation was just how destructive chronic inflammation can be. It isn’t always obvious, and it doesn’t follow the same rules as normal recovery. You might think you’re healing from a back injury, but if you’ve got something like mold exposure or Lyme driving systemic inflammation, you’re fighting a losing battle.

“Sometimes people can sort things out with the right postures, movements, and spine hygiene,” Dr. Jim explained. “But if the immune system is suppressed or constantly inflamed, tissues heal more slowly — or they don’t heal at all. That’s when pain becomes chronic.”

I’ve lived this reality myself. Back when I was chasing my all-time world record squat of 1,306 pounds, I thought I could simply outwork the pain. But eventually, I reached the point where my body completely shut down. I couldn’t even unrack my opener at a meet. That’s when I realized it’s not just about training harder — it’s about respecting recovery, managing stress, and addressing the underlying causes of pain.

The Brain on Pain

One of the more fascinating parts of our talk was when Dr. Jim explained how chronic back pain can actually change the brain. Researchers studying brain volume have found measurable thinning in certain areas of the cortex in people with long-term pain.

“People with chronic back pain often feel slower, more irritable, more fatigued,” he said. “And it’s not just in their head. Volumetric studies show that the gray matter — the outer layer of the brain — can thin in specific patterns. What’s really interesting is that when patients get the right treatment, and the pain is resolved, the brain can actually restore some of that lost volume.”

Think about that for a second. Pain doesn’t just live in your back. It changes how your brain functions, how you think, how you feel, and even who you are day-to-day. That’s why it’s so important to get to the bottom of what’s really causing pain rather than masking symptoms or assuming it will simply fade.

Pattern Recognition and the Human Side of Healing

When I asked Dr. Jim how he manages the overwhelming complexity of pain — with its seemingly unlimited causes — his answer was telling. “Yes, there are infinite ways people can end up in pain,” he said. “But if you categorize things, it becomes manageable. With the training we get from BackFitPro, we’re able to use touch, observation, and physical testing to understand the biomechanical side. Then, looking through the lens of inflammation and immune health, you start to recognize patterns. The more cases you’ve been privileged to see, the more effective you can be at helping people.”

That really hit me. As a coach, I’ve had my fair share of athletes with unique presentations. Sometimes the solution is simple: fix their mechanics, teach them how to move better, and they’re back on track. But other times, it feels like you’re peeling an onion — uncovering layer after layer of stressors, injuries, and hidden issues like inflammation or illness. That’s where collaboration with experts like Dr. Jim makes all the difference.

Final Thoughts

Chronic pain isn’t always just about the spine. Sometimes it’s inflammation. Sometimes it’s an infection. Sometimes it’s a combination of mechanical and biological factors that creates a storm the body struggles to calm on its own.

The key lesson? Respect the process, recognize the patterns, and never assume someone’s pain is “all in their head.” The nervous system, the immune system, and the musculoskeletal system are all connected. The more we can bring together experts across fields, the better we can help people find relief, rebuild resilience, and return to doing the things they love.

This conversation with Dr. Lysander Jim was a powerful reminder that healing takes both precision and compassion. If you’re an athlete, coach, or clinician dealing with pain or helping others through it, you won’t want to miss the full discussion.

Article Rundown

- In 2013, my back was shattered, and no therapy or treatment gave me relief.

- Dr. McGill’s assessment and no-nonsense framework finally made sense of my pain.

- By applying his methods, I rebuilt myself and squatted 1,306 lbs—the heaviest in history.

- Today, I pass those same principles on to lifters and everyday people rebuilding from injury.

A Meet That Changed the Game

Some memories never fade. For me, one of those is the 2011 Pro-Am in Covington, Kentucky. That meet was something special. Donnie Thompson totaled 3,000 pounds—the first man in history to do so. Dave Hoff was on fire, putting up an all-time world record total. Laura Phelps hit all-time marks in the squat, bench, and total. AJ Roberts set a total record as well. It was one of those rare days when the air feels different, almost electric.

People used to joke, “There’s no gravity in here today—the weights are light.” That’s exactly how it felt. Everyone was on another level. I had my moment too—squatting 1,185 pounds at 275, my second all-time world record squat. I edged Hoff that day and took home a $1,000 prize for the best squat pound-for-pound overall.

Donnie himself squatted 1,265 at over 400 pounds and became the first man to total 3,000. It was legendary. The kind of meet that reminds you why you fell in love with this sport.

Donnie’s Question

Fast forward to now, years later. Donnie asked me something recently that stopped me in my tracks: “Brian, why do you promote McGill so much?”

It’s a fair question. Donnie has been around longer than almost anyone, and he’s seen fads come and go. He’s seen lifters bounce between rehab approaches, gimmicks, and quick fixes. So when he asked, it wasn’t criticism—it was curiosity. And I think my answer is worth sharing, because it gets to the heart of not just my career, but my life.

Hitting Rock Bottom

Back in 2013, I was done. My sacrum was literally split down the middle. My discs were flattened. I had endplate damage at L5 and L4, and pain every single day. I couldn’t sit, couldn’t train, couldn’t function. I tried everything: chiropractors, epidurals, nerve root blocks, endless NSAIDs, until I ended up in the hospital with kidney stones. I foam rolled, stretched, hung upside down, and did all the “PT handout” exercises that don’t fix the cause of pain.

None of it worked. Everyone gave me pieces of advice—some good, some bad. Dave Tate told me to take time off. Amy Bernstein told me I needed to move better. Both were right in their own way. But without a system, without understanding how my spine worked, their advice didn’t land. Time off just made me feel worse because I was still moving poorly. And I didn’t yet understand how much movement, posture, and mechanics dictated pain pathways.

I was broken, frustrated, and running out of answers.

Meeting McGill

That’s when I met Dr. Stuart McGill. From the first assessment, it was different. He didn’t waste time. He didn’t coddle me. He told me flat out, “I can probably help get you out of pain. But lifting 1,000 pounds again? You’re done.”

I pushed back. I wasn’t willing to accept “done.” We went back and forth, and finally he relented: “Fine. Get pain-free first. Then we’ll see.”

That was the turning point. For the first time, I had a framework that made sense. Instead of masking symptoms, we identified triggers and removed them. Instead of stretching and flailing around, I learned to move with precision. Instead of hoping for a miracle, I started respecting my spine and building capacity step by step.

From Broken to History

The results were undeniable. I rebuilt myself. I got out of pain. I came back at 242 stronger than ever, hitting PRs across the board. And on October 3rd, 2020, I became the first person to squat 1,306 pounds—the heaviest squat ever done in competition.

That journey is why we wrote Gift of Injury in 2017. It’s not theory—it’s a roadmap born out of my recovery. Stu brought 40 years of research and clinical expertise. I brought 30 years of under-the-bar experience and the reality of having to climb back from the brink. Together, we built something that works.

Since then, Gift of Injury and Back Mechanic have helped tens of thousands of people. I’ve seen it firsthand—athletes, lifters, and everyday people who thought they were finished, now moving pain-free again.

Rebuilding Others

I’ve worked with lifters like Naomi Sheppard, who suffered a compression fracture and ended up in the ER. We spent six months winding her pain down, rebuilding her step by step. She came back to squat over 500 pounds at 148. I’ve seen dozens of others return to lifting after catastrophic injuries using these same principles.

The McGill Method isn’t about the Big Three alone. It’s about assessment, identifying the true causes of pain, removing them, and then progressively restoring capacity. That may include body tempering, chiropractic work, distraction, or other tools. It’s not dogma—it’s principles applied to the individual.

Why I’ll Always Promote McGill

So when Donnie—or anyone—asks me why I promote McGill so much, the answer is simple: because I lived it. He rebuilt me when I was done. His methods gave me the tools not just to lift again, but to set the heaviest squat in history. And those same tools now help me rebuild others—whether it’s a world record holder or a dad who just wants to pick up his kid without pain.

This isn’t marketing. It isn’t hype. It’s an obligation. I’ve seen what works and what doesn’t. I’ve lived the difference between “just take time off” and truly fixing the cause. I owe it to the lifting community—and to anyone struggling with back pain—to keep carrying that message forward.

That’s why I’ll always promote McGill.