28 May Deloads and Overtraining: Why You Should Embrace the Hated Deload

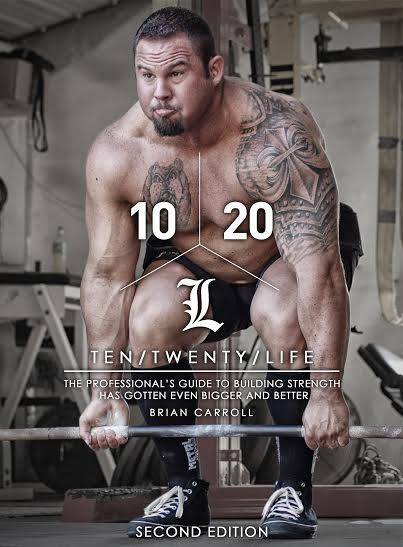

By: Brian Carroll

EMBRACE THE HATED DELOAD?

One of the most talked about and criticized training strategies is the deload. The topic of “deloading” gets thrown around constantly by social media gurus and everyone always seems to have a opinion. Either you are a huge pansy for even thinking you need a deload, or you run the risk of “burning out” your CNS if you don’t have a deload constantly every other training day. There’s not much of middle ground either way.

But do I use deloads in my own training and with clients? YES I DO. I’ve been lifting and competing for over a decade at the highest level of the sport of powerlifting, and I’ve seen both sides of the coin. Having gone through countless training cycles myself, and programed many more for other top athletes, I’ve learned the hard way how training without recovery can beat you down past the point of no return. And in most cases, this is entirely avoidable with a properly planned “deload” week.

Lest someone accuse me of being a pussy for believing in a deload (ignore the fact that I’ve squatted over a 1000 pounds dozens of times in competition and have been ranked in the top 10 alltime in 3 weight classes) understand that when it comes to strength building and training, my mentality is a practical one. Don’t “tell me” what you think is possible or what you think works, SHOW ME what does work. If something works on myself and my clients, I’m inclined to believe that that something is to be considered effective, regardless of whether the latest studies on PubMed support it or not. Common sense is warranted though, and I like the idea of combining some science with real world experience. That’s why I’ve learned from some of the best science minds in the game, like Dr. Stuart McGill and John Kiefer. I respect learning in the lab as much as the gym though, and that’s given me a perspective in the middle, with the best of both worlds.

DOES OVERTRAINING EXIST?

Call it under recovery, under resting, over peaking, under something, but regardless of name, overtraining can and does exist, and I have experienced it and CRASHED hardcore in my own training from it. One particular time in 2010, right before a meet, I peaked far too early, and ended up having a disaster of a meet. To preface this, I was stronger than ever at the time, but I was also pushing harder than ever, and by peaking too early, I went downhill FAST. I’m talking about insomnia, weight suddenly feeling overwhelmingly heavy that I was smashing weeks before, no appetite, depression – which faded as soon as I backed off for about 3 weeks. Problem was that this was the WORST timing for a deload ever, the week of the meet and meet day came –it was too bad so sad. I bombed out and it was entirely my own fault. I use the analogy of training be a process of learning to ride UP a wave, but in this particular time, I felt like a Giant wave was coming DOWN on me. And I was a helpless beach house being swallowed up by a tsunami.

It wasn’t until 3 whole weeks had passed, including 2 weeks of doing nothing but resting (along with the dogshit that was meet week) that I finally felt great again. I did a mini training cycle and hit a different meet soon after. I actually put up some pretty nice numbers, but I was not nearly as good as I could have been 8 weeks prior.

From my own experiences with myself and with clients, once you’ve hit an overtrained or overpeaked state, it takes about 2-3 weeks to fully recover from this. But don’t think you’re overtrained because you trained hard for a week. I’m talking 2-3 months of ball breaking effort every time you are in the gym. For the average athlete, once you’ve blown past your peak, the likelihood that you can push through it or still turn it a great performance is very low.

My unfortunate lesson from my own crash and burn came from believing I could brute strength my way through being under recovered and peaking too soon, and it turned out terrible. So lesson learned, I changed the way I approached my training. Rather than take time off from training so I could recover, I would regularly deload my training so I could train harder, and avoid peaking too early or crashing like Id done before.

RECOVER LESS, LIFT LESS

Before following a program like the one I lay out in 10/20/Life, I was as guilty as anybody of ignoring how my body felt and not taking proper care of my myself. Too many people make this same mistake, and it can derail a whole training cycle and cost you your performance on the platform.

Without adequate recovery, progress is going to stall at some point, and you will more than likely backslide. Rather than have a crash creep up on you and be forced to react to it, here are some things to consider that can help you avoid having to REACT to being beat down in the first the place. This is called listening to your body, and being aware of the following:

** Where you are in training – how many weeks in and how heavy you are going?

– Is this a meet training cycle or in the offseason?

-When was your last “down week”?

-How is your diet?

-How consistent is your rest and sleep schedule?

-What are your stress levels outside the gym? Family drama, drinking every night, relationship trouble?

-How on point is your supplement protocol?

-How many weeks have you been redlining it in training?

RECOVER MORE, LIFT MORE

After my own experience, I had to decide when and how to program a deload week. I decided a full week deload should do the trick every third week. Why every third week? This was something that just clicked with me. Why ride the line too much and get beat down more often than necessary? Why not take breaks or downtime/lighter days BEFORE they are necessary?

Since someone is going to mention it, I’ll address it first. I’m very aware of the positive compensation effect that comes with some degree of over training, but there is also point of no return like I wrote of above, so the premise here is to provide you with a basis for when to back off BEFORE you go into those waters and drown. By deloading every third week, you always be on top of managing your fatigue and stress, versus letting these things manage your training.

Deloading every third is an almost fool-proof way of avoiding the beat-down doldrums, and whether you want to call it a deload week or not, consider the following:

1. Think of the deload week as a TUNE-UP week. You back off a bit intensity or percentage wise, dial in your form, are able to simply focus on technique and approach, speed and tweaking the LITTLE things that typically WILL NOT be addressed or be as much of a focus on heavy days, especially when closing in on a test day or meet day, heavy day with your boys or girls, or simply just working on getting strong as f**k.

2. A mental break-the stronger you get; the more the weights can get to you. The down week keeps you mentally fresh and always looking forward to pushing the pounds throughout the whole training cycle

3. A Physical break-heavy weights can beat you up, no doubt about that. The deload will prevent this from damn near ever happening

4. Address all your weak points-Weak points can hold you back. The deload week is the time to hammer your core with the McGill big 3, work your upper back, do some targeted pump work, and focus on whatever particular muscles might be holding back your lifts

Training 24/7/365 full-bore balls to wall does NOT stand the test of time. You will hit the wall eventually.

MY PERSONAL RECOMMENDATIONS…

I don’t care if you hate the phrase “deload”, think overtraining is a complete farce (who knows, maybe??) but for god’s sake, call it an observation week, tune-up week, a rest week a light week…. I really don’t care what you call it. Regardless, know that this system works and that you DO need downtime, especially when you’re pushing toward trying to be your strongest self!

So maybe you don’t want to follow 10/20/Life, but you still want some advice about how to program a deload and what to do on those days? Sure, I’ll help you:

For your “lighter” weeks then, consider the following:

1. Work on singles-make them explosive: maybe 50%(sometimes 60 %works) and do 5 singles or so and work on locking in form 100%. As form is locked in, make the final couple of reps fast and even faster as you nail all your cues and finish your working reps

2. Keep your assistance work similar to your normal stuff, but cut down the assistance intensity and consider doing higher reps on this day

3. Put down the barbell-consider using specialty bars on squat and deadlift day, and floor press on bench day

4. Address your weak points- just about all of us could stand to have a stronger core, more upper back muscle, a stronger low back etc.

5. Get your mind right-work on your approach, sharpen your mental game and study your form on video.

I may not totally convince you that you need to deload every 3rd week like I advocate in 10/20/Life, but again my whole point to writing 10/20/Life as to give you a set of tools, with parameters and safeguards to create your own training program with some scientific approaches, common sense, to help create a long strength career with real world experience that works.

Deloading is a long term strategy to creating lasting strength, not a short-term quick fix training hack to deliver bullshit magical results. Use it or don’t, but at the end of the day, you can either show that you’re strong, or talk about how strong you used to be. I’ll choose the approach that keeps me strong today, tomorrow, and for life. Decide how strong you want to be then.

Brian Carroll

Latest posts by Brian Carroll (see all)

- Protected: -Header Image Post Template 2024 - April 18, 2024

- Brian Carroll X Professor Stu McGill full interview 2024 - April 16, 2024

- Protected: -Video Post Template 2024 - April 15, 2024

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.